The Ising Model and its Cousins

The Simulations

Statistical mechanics studies how microscopic laws give rise to macroscopic behaviours. Why do we see liquids, solids and gases? Why do magnets exist? How can we manufacture new materials with novel properties?

To answer these questions, we can make computer simulations. Here we will talk about 2D lattice simulations — these are simulations done on a grid. Below, I will explain the interesting behaviour present in these simulations. If you want to play around with them yourself, here is a list of them:

N-Vector Models

Lattice Gases

Advanced Models

What is the Ising Model?

The Ising Model, named after Ernst Ising, is a simple model that can be used to describe all sort of complicated behaviour. The basic idea is that we have a grid, and at each point on that grid we have an arrow that points either up, or down. We will represent the up arrows by white squares, and the down arrows by black squares. This is a basic model of a magnet: each square in the grid can be thought of as a little bar magnet, with the north side facing either up or down.

The behaviour of the system is governed by three basic principles:

-

Arrows want to align with their neighbours

-

Heat causes the arrows to flip randomly — the higher the temperature, the more likely a flip and the more randomly the system acts

-

An external magnetic field makes the arrows favour a direction. The bigger and more positive the magnetic field, the more the arrows want to point up.

I have made a simulation of the two-dimensional Ising Model. You can play around with it here By changing the temperature and the magnetic field, you can see all sorts of interesting behaviour:

-

Phase Transition: At high temperatures, the grid looks very chaotic, an even mix of white and black squares. Yet as we lower the temperature, we get clusters, regions where every square is black or white. If you leave the simulation long enough, the whole grid will become either black or white. This is a phase transition, from a state of disorder to a state of order, and is analogous to the liquid–gas phase transition.

-

Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking: The Ising Model has a symmetry: if we flip every arrow, changing every black square to a white square and every white square to a black square, then the system is identical. At low temperatures though, we see that the grid divides into regions of all black or all white. These regions are not symmetric when we flip arrows, and so this is known as spontaneous symmetry breaking. This phenomenon is important throughout modern physics, and is responsible for both superconductivity and the Higgs mechanism.

-

False Vacuums: Set the temperature to be very low and then increase the magnetic field. The whole grid will become white. Next lower the magnetic field so that it is negative. Now if all the arrows were flipped, the energy of the system would be lower. But each individual arrow cannot flip, because it wants to align with all of its neighbours. The grid is now in a false vacuum. Eventually, enough arrows will flip and the whole grid will flip to black. But this process can take a long time — for a small enough magnetic field, it may take many times the age of the universe!

I first learnt about the Ising Model from An Introduction to Thermal Physics by D. Schroeder; this book gives a very clear introduction to the topic. More advanced material can be found in these lecture notes by David Tong.

More Complicated Models: The XY Model and The Heisenberg Model

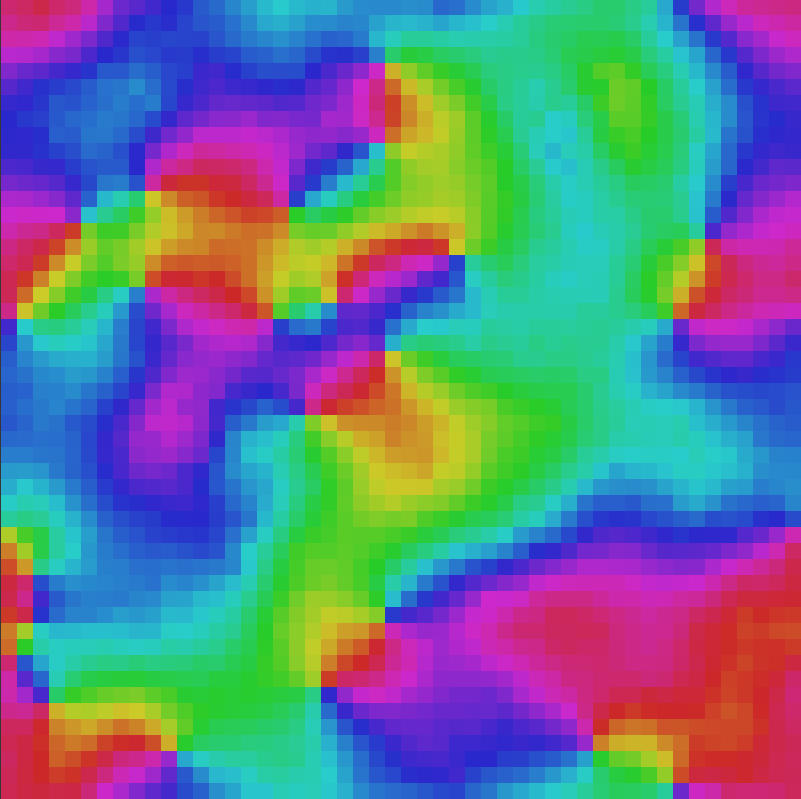

A simple to way to extend the Ising model is to allow the arrows not just to point up or down, but to point in different directions. We could for instance allow the arrows to take a direction on the circle, like the hands of a clock. We use colour to represent the direction — 12 o’clock is red, 4 o’clock is green and 8 o’clock is blue. You can play around with this model here.

One interesting feature of the XY model is that it has topologically defects, such as vortices and domain walls. These defects are important both in cosmology, but also in more down-to-earth applications such as liquid crystals and protein folding.

We can extend our model even further, allowing our arrows to point on a sphere, rather than a circle. We will colour the north pole white and the south pole black. Walking around the equator, we shall colour red to green to blue and back to red again. This is known as a color sphere. The model can be found here.

These two models are examples of n-vector models. They closely related to the more general non-linear sigma models, which are important in many fields of physics and mathematics.

Lattice Gases

So far we have thought of our simulations as describing magnets. But, if we make a few modifications, we can instead think of our simulations as describing liquids and gases.

The idea is simple. We can think of each white square as representing a molecule, and each black square as empty space. The molecules repel at short distances, so there can only ever be one molecule in each square. But, at medium distances the molecules attract each others, and so the white squares want to be neighbours. In a gas, the number of molecules remains constant, so the number of white squares remains constant in our simulation.

At high temperatures the white squares (ie the molecules), spread themselves randomly throughout the space. But, as we lower the temperature, the molecules clump together into droplets — the gas condenses into a liquid!

One way to make the simulation more interesting is to add gravity — a force attracting the molecules to the bottom of the page. You can play with the lattice gas here

Oil and Water

Oil and water do not mix. We can simulate this using two different types of molecules. The white squares are water molecules, and they attract each other. On the other hand, the yellow squares are oil molecules, and they do not feel any attraction towards the water nor other oil molecules. You can mess around with the system here. We can now see that the oil and water molecules tend to separate, just like in real life!

Advanced Models

A lot of statistical mechanics models exist, many with interesting properties. The Tricritical Ising Model is a modification of the Ising Model, where lattice sites are allowed to be empty. This means that the number of atoms can vary in the model. There are three different phases, which can coexist at the critical temperature — hence the name.

The Potts Models are a family of models which generalize the Ising model. In these models, there are q possible values at each point in the lattice; when q is two this gives the Ising model.